Do lower-emissions companies have higher valuations?

Responsible investing has become so widespread in financial markets that virtually every investor thinks about the climate or social impact of their investments.

However, the effect this culture shift has had on asset prices remains somewhat elusive and hard to measure – particularly in a market as small as New Zealand, where direct comparisons between companies are hard to find.

In a 2019 carbon report, Forsyth Barr’s equity research found that lower emissions companies, on average, have higher valuations than high emitters.

The analysts warned the valuation benefit may be coincidental, but it matched the trend in data from international markets.

“Emissions are clearly not the only driver of valuation; however, the broad relationship across different markets suggest investors are willing to pay more for low emitters,” they wrote in 2019.

Forsyth Barr is preparing an update to this piece of research, which will likely be released towards the end of this year.

When BusinessDesk charted more recent data, it found no strong correlation between emissions and valuations for companies listed on the New Zealand stock exchange (NZX).

The highest emitters – those with more than 5,000 grams per dollar of earnings – have the lowest average price-to-earnings ratios, but low-emissions companies have lower average ratios than middle-emitters.

Forsyth Barr’s 2019 data showed a clearer correlation, with the lowest emitters also having the highest average valuation.

Even in energy

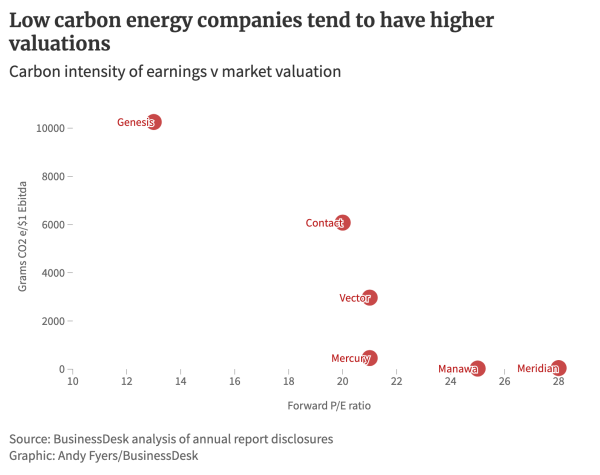

The correlation appears strongest when charting NZX-listed energy companies, with the cleanest electricity producers also having the highest valuations.

Genesis Energy – which operates a coal-fired plant in Huntly – has the lowest price-to-earnings ratio and the highest rate of emissions per dollar earned.

Low carbon energy companies

However, even in this case, it's very difficult to identify the exact impact of carbon emissions because investors are weighing up many other elements in market valuations.

Barry Coates, chief executive of Mindful Money, said it was highly complex to measure the exact impact of carbon on valuations.

Comparisons would need to be made between near-identical businesses to make a definitive, academic conclusion, he said.

However, Coates said some institutional investors who reduced emissions in their portfolios have reported improved returns.

“Managing climate risks is good financial management. Companies that do so are increasingly being rewarded by financial markets for doing so,” he told BusinessDesk.

Global greenium

A United States National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, published in February last year, analysed the pricing of carbon risk over 14,400 listed companies in 77 countries.

Authors Patrick Bolton and Marcin Kacperczyk said: “We have found evidence of a widespread, significant, rising, carbon premium – higher stock returns for companies with higher carbon emissions.”

Bolton and Kacperczyk said the carbon premium was found across all sectors and continents. The analysis included 50 stocks from NZ, although did not focus on them.

The authors said the higher stock returns for lower-emitting companies didn’t relate just to direct emissions, but also indirect emissions through the supply chain.

Bolton and Kacperczyk said the carbon premium has been increasing since the Paris accord of 2015 and as the sustainable investment movement has gathered momentum.

On the other hand, two researchers from Stanford University analysed green bonds in the United States and found they received no carbon premium – which they called "a greenium" – in the market.

“Comparing green securities to nearly identical securities issued for non-green purposes by the same issuers on the same day, we observe economically identical pricing for green and non-green issues,” David Larcker and Edward Watts wrote.

This research was limited to bonds issued by US municipal government entities, but the authors argued its findings could be applied in other markets.

“If a greenium exists, we believe that the municipal securities market is a setting where it is most likely to be observed,” they wrote.

Larcker and Watts said this was because municipal markets were so small that a green investor could easily be the marginal trader pricing the asset.

This article was originally published by BusinessDesk.

About the author

Dan Brunskill is a journalism graduate from Auckland University of Technology who joined BusinessDesk in 2020. Formerly a photographer, he took up journalism as the news editor of Debate Magazine before going on to work at the New Zealand Herald.